|

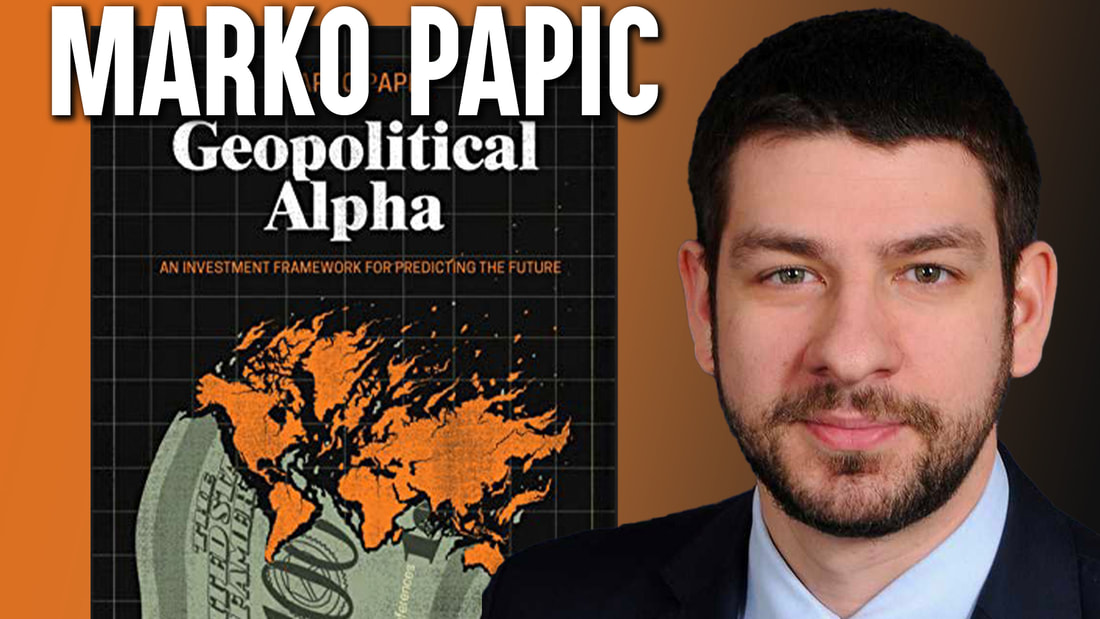

Marko Papic leads the strategy team at Clocktower Group, an alternative investments firm. Clocktower offers long-term strategic investment strategies to their clients, investment managers and institutional allocators.

Marko brings his constraints framework, outlined in his book Geopolitical Alpha, to analyzing the geopolitical trends of the day. His ability to accurately forecast major political events has enormous ramifications for portfolios. In this episode, Marko and Aaron discuss how the future of China-US conflict, Turkey’s geopolitical prospects, and how to break into the geopolitical analysis field. Sign up for a Weekly Email that will Expand Your Mind. Marko Papic’s Challenge; Spend time around people with the opposite political and cultural perspective of you. Connect with Marko Papic

Linkedin

Geopolitical Alpha book If you liked this interview, check out our interview with Mike Green where we discuss Bitcoin and index funds. Text Me What You Think of This Episode 412-278-7680

Underwritten by Piper Creative

Piper Creative makes creating podcasts, vlogs, and videos easy. How? Click here and Learn more. We work with Fortune 500s, medium-sized companies, and entrepreneurs. Follow Piper as we grow YouTube Subscribe on iTunes | Stitcher | Overcast | Spotify Aaron Watson: Well, Marco, thanks for coming on the show, man. I'm really excited to be speaking with you. Marko Papic: Absolutely! Same here. Real pleasure. Aaron Watson: So, I want to start off just explaining for folks specifically, the, the role that you play at the Clocktower Group, maybe a little context of the Clocktower Group generally. And then, we can kind of move into this really, really good book here, Geopolitical Alpha, the concepts, the, the impetus behind it. But to start off, what's the kind of role you play in this financial firm? Marko Papic: Sure. So I'm a, I'm a partner and a chief strategist at an alternative investment management firm. We're based in Santa Monica, California. And what we do is we specialize in turning macro big picture ideas into you know, relatively illiquid alternative investment strategies. So those would be, for example, seeding macro hedge funds or investing in early stage fintech companies around the world. We've just launched a fund dedicated to Latin America. In that particular sphere. And also we have interesting businesses in China. We're also taking our approach to seeding macro hedge funds, and we're taking that to China. So most people, when they think of macro investors, they think of investors that deal with, you know, public markets that trade copper or dollar these kind of big asset classes. We also think about big ideas, but we didn't articulate it in these kind of illiquid strategies. Aaron Watson: And mostly if folks were trying to wrap their head around the client that you're serving, it is the capital allocators at some form of a large institution, be that an endowment or some sort of, you know, pension system or something like that. Marko Papic: Yeah. So it would be institutional investors, exactly what you're describing. And that's because, you know, you know, retail investors are not going to have the patience and the mandate for something as exotic as these illiquid strategies. But also in the U.S. In particular there's a lot family offices that would be the kind of investors that would do this in family offices, of course, are high net worth individuals that have basically an office managing their assets. They would, they would also be interested in, in private delegation or illiquid allocation. Aaron Watson: Gotcha. So the reason I was so excited to have you on, as we've discussed previous to the recording, I really enjoyed the book, Geopolitical Alpha, and outside the context of how someone might know me professionally, which is, you know, we're helping people with media production and marketing my kind of Intellectual recreation is usually around geopolitics. And so being able to come at the world of investing with this geopolitical lens is a very kind of interesting intersection of ideas that we explore on this show. And just perhaps a framework that people aren't as used to incorporating into their investing strategy. Maybe they'll say, "Hey, I'm going to go into emerging markets," or "I'm going to have a U.S. Centric index fund that I'm investing in," but really having to have a, a sharp edge to the tools with which they are evaluating the geopolitical changes of the day is becoming increasingly more relevant than I think that's why he wrote the book. That's why you've kind of found yourself in this position. Can you talk a little bit maybe give you a little bit of a history lesson as to why that's becoming so salient, and then we can kind of move into the constraints framework that you're using. Marko Papic: Yeah, sure. Well, I think what's happening. I mean, first of all, someone with my background and my skillsets and my methodological bias would likely not have a job in finance, you know, 20 years ago or 30 years ago. And that's not entirely true. Macro hedge funds have always been very sensitive to politics and geopolitics. But for, for a run-of-the-mill, you know, investors, usually do not have to concern themselves with these issues. And why is that? It's very simple, because we adopted the west adopted a set of policies, a set of best practices they had to do with macroeconomic policy. So for example, fiscal policy should be countercyclical. That means you only really stimulate when there's a recession. Or monetary policy became very orthodox, very focused on, you know, a preemptive rise in interest rates, and the first sign that the economy is overheating. Free trade, you know, became kind of a best practice laissez-faire economic system, where the government takes a back seat to regulation or industrial policy. All of these were really established in the eighties. And this is a really important period of time because the 1980s saw the world leave a very turbulent decade where inflation had overshot expectations where policy was largely incoherent. There was a lot of unorthodoxy that led to suboptimal outcomes. You know, we had very high rates of inflation throughout the 1970s. And so the way to curb that, of course, Paul Volcker raised interest rates, which is a very foundational moment for many people's careers in finance. And at that point, 1980s saw this adoption of these best practices that many economists and journalists and kind of professors have dubbed the Washington Consensus. That was a really, really important moment in history. And then from 85 to 90, the Soviet Union collapsed. So as the west is adopting these policies of capitalism, the alternative, which is institutionalized socialism and communism, collapses. And so then the rest of the world says, well, which, which system works, we'll take the Washington Consensus. And that's what the IMF and the World Bank starts propagating the set of best practices around the world. So what's changed? What's changed is that those best practices after 2008, after the great financial crisis and awkward this year have been brought into question. And that means that fundamentally the government got pushed aside by those best practices, the role of government and finance and economics it's coming back. And that's where politics and geopolitics are now. Again essential to being an investor and not just a fancy hedge fund trader, but like if you're an investor, you have to have some understanding of politics and geopolitics. Aaron Watson: And the framework that you introduced in the book, you talked about it being a constraints based framework and on all sorts of previous conversations we've had on the show, we've talked about constraints is very familiar probably to the people listening to this, but usually in the context of their business. So, you know, it's hard to find the marginal additional talented person to employ or cash flow or distribution for their message or all these things that small business owners are very, very accustomed to having to negotiate. It's all constraints informed. Can you talk, you know, that's more of like a micro level. Can you talk about when we take that up to a macro level and evaluate a nation state, how that same idea of constraints is applied to these much, much larger entities? Marko Papic: You know what, I'll, I'll explain it from a different perspective that I don't think I've ever really used to explain this before. There's really two sets of groups of people who analyze geopolitics. There's policy makers, like, who are in the game. They're within the same realm. And so they rarely think of constraints because it's a little bit, like, ego deflating. If you know, you overlook constraints in other policymakers, because you don't want to believe them yourself. So, and what this means is that very rarely is an intelligence agency of a sovereign nation state to say, ah, don't worry about it. You know, they're constrained. They focus a lot on what policy makers want to do, what politicians want to do. So if you go to an, a former member of the intelligence world or a former politician, they're rarely going to talk to you about what they can't do because they've spent their whole lives, trying to overcome that. And you know, like, like that's why we elect many of these people. That's why we hired them. So did they came to do better than your constraints? And so they're wired in a certain way. Then on the other side, you have the investment community that when, when the investment community tries to do approach goepolitics again, because the last 40 years were so clear for many investors, what they needed to learn and they get basically needed to get a CFA. They needed to know how to value things, you know, mathematically, like it became very mathematical routine, kind of a job that very few of them really looked at geopolitics and politics in a systematic way. And so they started to think of geopolitics as a realm of food, where you got to go and find a former politician to tell you what's happening, you know? And so you had this real mismatch in cultures where on one hand, investors are extremely systematic, frameworks driven, objective, quantitative. But when they're faced with geopolitics and politics, these suddenly become like chicken on trail readers, you know, and they, and they visit these websites. And I don't want to name, but are really, really subpar in the kind of information they're giving you. It's basically conspiracy theories. And I found this really fascinating when I joined the financial industry, I was like, "Really?" Like, "You'll read this crappy blog to find out what's going on in the world. And yet you're so focused on systematic framework driven approaches in finance?" That was bizarre to me. And so, what I settled on is just focusing on constraints because they're observable, they're quantifiable. And because in my experience, you know, preferences are both optional and subject to constraints. Whereas constraints are neither optional nor subject to preferences. And that goes back to your example, which is like, if you're running a business, you can wish to have more cashflow to hire more people. You can desire it, but that's your preference. The reality is the constraint. And then you operate within those constraints. And that is a tool for forecasting politicians, policymakers, as good as we have available to us. Aaron Watson: Yeah, I would love the Nike advertising and marketing budget, but just because I want, it doesn't necessarily mean that that's going to be able to come into being. Marko Papic: Exactly. Aaron Watson: So just to maybe get a little bit more specific, and then I kind of want to go around the world with you and talk about the kind of practical application of this framework to a couple of different elements of geopolitics. Some of these constraints might be, or correct me if I'm wrong. You know, the, the general kind of sentiment of voters. So it doesn't matter if you want to do something wildly to one extreme left or right. If there's kind of a, a median voter or the average consensus of the voters, you can't stray too far from that without exposing yourself to real risk in non authoritarian dictatorships. There's the core geography of the country. There's the demographics, how old or young and the general skill, what other kinds of constraints when you're looking at a country? Not that you're going to discover a new country necessarily, but when you come to it analyzing country, what are the main things that you're honing in on? Marko Papic: You know, it really depends on the question you're trying to answer. So if I'm trying to forecast weather, like, Russia is going to militarily invade Ukraine again, you know, there's one set of constraints specific to that issue. If you're trying to forecast whether India is going to be able to do pro-business structural reforms, there's a set, there's a different set of constraints. And the book kind of like as you list yourself, the good, the book goes through all of these. And I give empirical examples. I give examples of how these constraints work in, in, in reality. I guess what I would say for listeners of this podcast though, I would just kind of like bring you back back to the kind of like big picture and simply simplify it to this. If you can measure it, it's a constraint. You know, if you have to read a book about some politician's views, it's not a constraint. So I'll give you an example of this, like 2016, 2017. I went in, I was working in what's called south side research. I was working at a different firm and I was producing research for investors. And so I would go on these road shows where you go and you basically pitch your, your wares, your, your views and ideas. And I went to Asia, you know, Hong Kong, Singapore China, Tokyo, and I, we were talking about the trade war and everyone told me now we're good. We're not worried. Okay. You're not worried about the trade war? Why is that? Well, because we read The Art of the Deal, the book that, you know, Donald Trump wrote, and we know what's going to happen. It's all good. Don't worry about it. Like, we're good. And I was like, oh, really? So you read a book and that makes you feel confident that Trump is not going to pursue a significant trade war? Like yeah. Yeah. He's not really serious. He's just, you know, trying to get a little bit of better terms. And I was like, "Yeah, this isn't about his preference." The median American had moved against laissez-faire economics, had moved against free trade. And we had the data to back this up. This wasn't about Trump's preferences. He was simply a political vessel for the American media voter to express their desire, to have basically, you know, confrontational view, a much less openly globalist policies. And, you know, he was just the right person for the right time. But yeah, this kind of like a nonchalant, well, don't worry about it. There'll be a little bit of a scaffold and nail here. He'll get a deal with China. Like, turned out to be really wrong. We were headed for a recession, even before COVID, largely because the animal spirits had sapped from the economy. You could see this through numerous of indicators because the trade war had been much more significant than people thought. And that's a great example of how even the smartest people who make a lot of money and they have great education overemphasize the ephemeral, the qualitative, and it really reminds me of that scene from the movie Moneyball I don't know if there's any fans of Moneyball here, but when Billy Bean is sitting around surrounded by these octogenarians you know, baseball scouts for talking about baseball players, based on these completely qualitative indicators, like this ballplayer player is not going to be good because he has an ugly girlfriend. That's literally a scene in the movie. And you're just like, wait, what does that have to do with how, oh, it shows a lack of confidence, you know, like, okay, maybe that flew in 1963, but that is a non-diagnostic variable. And you will be surprised how many people in positions of serious power who manage a lot of assets, make the same kind of statements about politics. It's just not systemic, no framework. Just I read a book or I read a blog. Aaron Watson: Yeah. Speaking of the ephemeral, at least to me, it feels like there is a new headline or something associated with the Strait of Taiwan and some ship sailing through. And that being basically pointed to as the potential flash point or hot point associated with rising tensions between the U.S. And China, but at the same time, one, one thing you did a really great job in the book of talking about was the actual constraints of popular consensus that still affects the Chinese Communist Party, despite a less sophisticated person looking at the, well, either a single party, they've got no competition. Why would they have to worry about public sentiment, but can maybe you bring the constraints framework specifically to tensions in Taiwan and the, you never going to say concretely, but the likelihood of things escalating there in some way, shape or form. Marko Papic: Although I would, I would. You know, like this is what I have to do for a living. So I, I would say overtly what, what the probabilities are. I mean, I think I would say the probabilities of conflict between U.S. and China or let's say co crisis, some sort of a crisis, you know, Berlin Crisis, Berlin Airlift Crisis, or Cuban Missile Crisis are good analogies. I think the probability over the next six months is, is actually quite high. I would say about 20%, which is significant, you know, that's, that's like a, basically a one in five chance that we have some, some crisis that is derived from the, the, the tensions in the straits of Taiwan or, or just South China Sea and so on. Why is this? Well, because I think China is adjusting to a new America and, you know I think it was relatively easy for Beijing to to, to, you know, like interpret the, the, the Trump administration as an anomaly. But now that the Biden administration is doubling down on many of the same sort of pieces of rhetoric, but actually making it even more uncomfortable for China by stressing human rights and stressing geopolitics, which Trump didn't really do until 2020 it's it's going to cause the period of adjustment. And China is adjusting to this new rhetoric and strategy. This reality that the U.S. and China are indeed rivals. And so in the near term, I would say the probability of a crisis is, is elevated, but I think it will dissipate and then we'll have this interregnum. So once we've passed the first six months, all the adjusting to a new administration, I think us and China will settle into some sort of, you know, more stable equilibrium. And then only in the longer curve can the probability of conflict rise again. If, if China does manage to, you know, rival the U S in terms of raw geopolitical power, so it's a U-shape probability. Now, why does it dip? Why doesn't it just increase linearly? Well, because of the constraints that I think many commentators are just completely ignoring. And there's two sets of constraints, what is a mega constraint, which is the fact that we don't exist in a world where only China and the U.S. matter. There's other countries with significant independence in pursuing their foreign and economic policy. And you might say, "Well, I mean, that's always the case." Well, no, it's not in 1945. I can tell you, there were only two countries on the planet. The matter there was Moscow and there was Washington DC, nobody else got asked anything. You know, like us sort of like kindly asked London and Paris what they thought, but not in a serious way. In fact, when France or the United Kingdom tried to pursue an independent foreign policy in the Suez Crisis they were threatened by the U.S. to back off because it was causing problems in its relationship with the Soviet Union. So the bipolar nature of the Cold War, or it's something that's unlikely to be replicated the us and the Soviet Union had incredible hold on their allies. I wouldn't even call them allies. They were really vassal states, you know, NATO and the Warsaw Pact were not alliances of equals. They were. You know, there was the center and then the periphery. Today, China, the U.S. are nowhere near the same level of power in relative terms. And that means that the constraint on the two of them carving up the whole world is that their own allies are not going to abide by their policies. So imagine in a world where the U.S. for example said, "Okay, you know what, we're going to stop trading with China." You know, the Congress Department says to Boeing, "Hey, no more selling airplanes to China." What's going to happen? Like, is Airbus going to follow the United States? Of course not. There's no way. France is going to say like, "Oh, that's a cool story. We're going to go and sell them more now airplanes. Yes, that's awesome." And this is by the way, what happened in the 19th century, precisely the same dynamic happen. And you had this world where Germany continued to trade with the UK, France, and Russia, because those three countries couldn't coordinate on these matters on their own. So that's the first constraint. The second constraint is what you alluded to, which is China itself is constrained in being extremely assertive. A lot of the policies that are emanating from Beijing suggests that they're moving towards a more consumer-based society. And one of the reasons that - economy - consumer based economy. And the reason they want to do that is they want to become more independent. They don't want to rely on the American consumer demand or economic growth, but that's going to take time. And last year, and this year it's exports that have led the recovery in China. The household spending has actually been hit quite a bit. China did not stimulate its economy the way we did. There were no stimulus checks kind of flowing into the Chinese economy. And so if China wants to have economic stability, it's going to have to play ball with the rest of the world because the end consumer, the final demand, is still external to its economy. Even as its exports, a share of GDP has fallen. So China has this real difficult balance. It's not ready yet to become, you know, fully assertive. And I think a lot of the commentary, especially in theU.S. Overstates both Chinese assertiveness and its ability to be as aggressive as people think it will be. Aaron Watson: Yeah, that makes a ton of sense. As a, as you talked about those different analogies, you know, thinking cold war and vassal states either aligned with the Soviet Union in the U.S. I almost thought more like American football where it's kind of the head coach and everyone is just pieces on the head coaches board in terms of where they might move and this multipolar environment where there's maybe two stars. If, if you want to call China and U.S. the stars but all these other capable, independent actors, more like a basketball game where maybe, you know, things rotate around the Steph Curry or the LeBron, or what have you. But, you know, some guy might just decide to go off and do their own thing and, and throw the entire game out of whack just because they have that autonomy. Marko Papic: You know what, like, listen, I'm a sucker for sports analogies, as you know, like you plant, like I can tell - the book is full of them. Some of them were funny, I think. So I would say that you know, soccer is a really good example of what we're collecting. You know, like I think basketball is perhaps a poor analogy itself. Do I see the Coca-Cola - coach point? Basketball is just like five, five dudes with the ball, you know, so like one person really does make a big difference in basketball, but soccer, like you can be the best soccer player in the world as Messi has been for the last, you know, like 10, 15 years. And yet you cannot really contribute to your team as much as Michael Jordan or as a coach in football. And that's the world we're in today. It's a world where the us is going to have to work, to get its allies on board on a number of different things. And I think one of the things that you've seen American commentators really tried to stress is the threat of China. And the problem with that is two-fold. One Japan has been living next to China think forever. And you know, I mean, Tokyo is sitting there and listening to Biden and Trump and like, "Really? You know, like that's really cool story. Yeah. We've been dealing with this for a very long time." So Japan is actually quite pragmatic, even after some serious confrontations with China that almost did lead to the blows, like in 2011 and 12, over to Diaoyu Senkaku Islands, you know, Japan has continued to trade and invest in China. Look, I'll bite that a lower trajectory, but Japan has, has learned to live with a very powerful in a certain China. And so they're not going to freak out over that overnight because suddenly America tells them to. And then you, and the other side Europe, which is so far away from China, you know, I see some of these comments, the theaters in the U.S. talking about debt-traps and so on. And a lot of this stuff is just honestly nonsense. No one, I feel like no one in Eastern Europe is worried about becoming indebted to China and then China showing up with a gunboats and seizing factories. And Europe is so far away that, you know, there's obviously concerns about property rights, intellectual property, about technology theft, all those things, but for Europe, Japan, even South Korea this, this new kind of verbiage out of America is just difficult to agree with. In other words, China would have to do a lot more to prove the U.S. correct in the eyes of the rest of the world. And that's why coordination against China is going to be much different from coordination gives the Soviet Union Aaron Watson: And so, that would kind of lead into people, very familiar with NATO as this kind of way of trying to block in the Soviet Union. And there's this similar noise made about the Quad: India, Australia, Japan, the U.S. kind of coming together to try to form a similar type of containment to China generally. And you would just say that that's not really going to operatein a similar way? Marko Papic: No no way. I mean, you know, like NATO has. Has a mutual defense clause which has triggered automatically Quad is nowhere near being that kind of a level of a military alliance. And so I think, I think it's just going to take a lot more time and it would, it would require China to, to make some severe mistakes in terms of foreign policy. So it's not impossible. For example, trying to reunify with Taiwan militarily would certainly accelerate some of these efforts. And then I think that would, that would change my my view considerably. But short of that, I mean, it's just, you know, there's, there's no level of threats that's equivalent and I'll give you an example of this. The Soviet Union had something like 70 tank divisions ready to burst through the Baltic gap, and take Frankfurt in like half an hour, you know? And there was actually no way conventionally, at least this was the thinking at the time, it was later revealed to have been perhaps a little too alarmist, but the conventional view, in the sixties, seventies and eighties, was that there was no way to prevent the conventional war against the Soviet Union. There was like no way to stop them. And so the United States did not have a no first use policy towards nuclear weapons. Why? Because he plans to use them in Europe who stopped Soviet attack, which tactical nuclear weapons, which were positioned throughout European continent. So the Union on the other hand was very magnanimous and they said, "No, no, no, we will never use first because we, you know, we'll be in Paris in a week." And so this was like not some sort of a theoretical threat. "Oh one day China will have dominance of 5g and then they'll spy on our kids through tick-tock and then our kids will be brainwashed," you know, like, no, no, no, no, no. There was a tank! A Soviet tank, like over there, you could see it and it was going to come over here. And so that's where NATO was born, you know? So like the equivalence here is, is, is honestly. Like comical, I'll give you another one. There were parties like political parties in Europe, in Paris, in Rome, in 1940s and fifties that owed their allegiance to Moscow. You know? So like this wasn't again, academic, this was actual parties. Oh, in loyalty to an enemy. And you know, the Communist Party of France, Communist Party of Italy, like, look it up. They didn't win elections, but they weren't like 20, 30% of the vote. So today, you know, people freak out about China, like you know, using money in different ways to influence people. Of course that's happening of course, but the level of like espionage and influence, which is much different. In fact, that's why the us launched the Marshall Plan to ensure that Italy and France did not turn towards communism as their operating system in the late 1940s and 1950s. And so Europeans who understand history and have experienced these, these geopolitical tensions. It's just going to be very difficult to convince the Italian government that there's this existential risk. Well, when it comes to China, it's basic. What's going to be possible. It's going to be possible to show up in Rome as a member of theU.S. State department and say like, look, China's like critical. You need to stop trading with them. It's just not, it's literally not going to happen. Trump didn't succeed, Biden won, and that's going to then create the constraint that American policymakers in how much they can really be leveraged from their own relationship with China. Now this doesn't mean the war doesn't happen. This is something very important. It sounds like I'm pretty dovish. It sounds like. I think that world's going to basically just sing kumbaya. The problem with that is that I'm absolutely historically empirically, correct? It's like the argument is practically unassailable, but my example from the 19th century, how did it end up. Yes, Germany traded with the UK would France and Russia right up until summer of 1914, and then it went to war with it. So that's something to just keep in mind that, you know, you can still have these nonlinear outcomes, even for the, even if for the next five to 10 years. You know, there may not be economic bifurcation between the U.S. and China, and that's something to keep in mind. Aaron Watson: So I'm going to spin around the globe again and touch on a couple of things you've said. So there's these very capable, other independent actors around the globe. And there's another country that has been a part of NATO, but has kind of been up to their own stuff, which is Turkey. And to me, this is at least in my reading of the news or my perception as an American, the biggest blind spot, generally for Americans, just in terms of influential actors elsewhere on the globe. You know, there's all the, all the drama in the Mid - Middle East with Iran. Obviously we talked about China and have an awareness of world war, you know, Europe because of learning about World War ll somewhat in our history classes, it seems like an enormous blind spot. I, I can't and don't even really know who I would talk to in my life about Turkey in some way, shape, or form. So can you kind of take us from like a rudimentary level up to the constraints and the challenges that Turkey's facing? Marko Papic: I mean, wow, Turkey's facing a lot of different cross-currents. I think Turkey is facing one of the largest mismatches between what it aspires to do and what its actual capabilities are. And so, you know, Turkey has a pretty advantageous geographical position between two key continents. It had great economic relationship with countries like Syria and Iraq to which it provides a lot of services, a lot of you know, manufactured and consumer goods. So it has a potential to be a pretty significant, you know hub of technological, consumer manufacturing, prowess, and it has a lot of potential markets that it could dominate because it understands those markets culturally linguistically in case of, you know, some central Asian economies and so on. At the same time, it has a real problem. And then real problem is that in terms of energy, it's completely dependent on Russia, more or less. It has really no imports, massive amounts of oil and natural gas. And then finally, it, it never really managed to integrate itself into the European economy because it did not really satisfy all the kind of political and sociopolitical, you know, rules and norms that Europe was asking it to do. And it. The fact that it's sort of an advantageous geographically almost as a detriment because it can't decide which sphere of influence to fit into. And it's continuously tries to carve out its own before it reaches a certain level of material wealth. And so that's what I would argue has been the problem with the policy of, of Ankara over the past 10 years, it chose to make a bid or a sphere of influence of its own before he was capable of doing so. It abandoned its bid for the European Union, thinking after 2008, 2009, while the West is declining anyways, why do we need them look at them? They're about to collapse. We're going on our own. All of those decisions were probably made even earlier than 2008. And they basically struck out on this view like, well, we're going to carve out our sort of proto sort of Neo-optimum sphere of influence that we had in the past, which is really north Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, Caucuses, and the Balkans. And the problem with that strategy is that it upset way too many actors, whether it's the United States, whether it's Saudi Arabia in some of its moves after Arab Spring in Egypt, whether it's Russia and basically all those attempts to carve out the sphere of influence have largely failed through the detriment of its economy. And it's a really good example of why geopolitical power ultimately rests on material wealth. You know, like, and a lot of geopolitical strategists, mis - mistake this. There's this view that economics is irrelevant for some, some, somehow subservient to geopolitics, to demographics, the geography, and Turkey is just a good example that you can have great geography and just be at the mercy of you know, actors around you that have a larger surplus that they can carve out of their economy and dedicated, to geopolitical endeavors. And so Turkey has just been biting off more than they can chew in a world where other powers still have a lot of interests. Aaron Watson: That's so funny. Once again, the analogies to like small businesses and startups, the ability to have focus versus kind of spreading yourself too thin on too many projects. Yeah. I'd argue that Uber was guilty of that, but some of the endeavors that they've pursued and they're kind of learning that lesson painfully now. I have one other question kind of, as we talk about places around the globe, and then I want to talk about this career that you found yourself in, how you got into it and all that good stuff. There's another idea out there, which is the notion of the rise of the city state, and maybe the sterling example of that is a place like Singapore, and, you know, you see attempts at this happening around the Persian Gulf. And, you know, even the, the, some hype, at least in like tech startup circles around Miami versus San Francisco and these other types of places. There's, I guess a somewhat arg- obvious constraint in that these city states usually cannot raise anything, resembling a substantial military to defend themselves. However, they do have some really substantial capacity for wealth generation. And so I'm curious if you kind of buy into that idea of the rise of the city state narrative or if you could maybe just talk as, as you think about those different types of endeavors, if you see them still as either vassals to a more powerful entities or the ways in which those types of frameworks are constrained. Marko Papic: You know, I think every period in history had city states or neutral places to do business. I don't know how to define it because you know, some of them are not necessarily cities, but they're like those little enclaves. So I think that I'm not sure that there's anything unique in history through the current mo - - moment. There are always places that managed to leverage their relevance, human capital, geography, and neutrality to the great benefit. You know, also like you think of Singapore today, you can think of Venice as well in the late middle ages. You know, so there are examples of this throughout history. You have the Switzerlands of the, of the world and by the way, Switzerland and Singapore have a pretty similar population, even though one is a country, the other one is a city state. So I don't think there's anything really unique about this. What's interesting is what gives rise to these entities. And I'm not sure that there's anything you need again about current conditions. You know, like you could argue that Singapore is very much leveraged to globalization. And you might think that in a world where we have de-globalization over globalization has kind of reached its apex. Maybe we won't have as many city states, but I don't, I don't think that's the case. I think that you will always have places in the world that because of their interesting mix of regulation, the human capital become, you know, important in some way. So Miami is a really good example because of advantageous taxation, because, because of a idiosyncratic really issue that most people probably don't think when they think of Miami, but after 2008, the United States cracked down on financial, safe havens on places where, you know, you could do tax avoidance. Where a lot of wealth was basically hidden, whether it was Switzerland, the Caribbean, and ironically, all this money basically flooded back to the U.S. whether consciously or subconsciously the U.S. created this incredible effect and, and a lot of it from the Caribbean and Latin America did go to Miami. And so I would, I would say that was the first step in this latest iteration of Miami that combined with low corporate tax rate would interesting, you know, multicultural scene. I think that's given to Miami, this rise that you're witnessing right now. I think this will always happen. I don't think it's unique to this current period. And, you know, it'll be interesting to find out which ones are the next ones. Aaron Watson: And, and they do to some degree make themselves a target by accruing that wealth and influence perhaps evidenced by the kind of absorption of Hong Kong by China recently, where if you are that kind of economic driver and some particularly powerful geopolitical forces nearby, you, you kind of put a target on your back. Marko Papic: But I'm not sure that Hong Kong is going to dissipate as, in terms of influence. I mean, I've changed my view on this. I've written some reports where I've said it will. I mean, you know, it depends. I actually think, you know, Hong Kong could continue to be relevant, especially in a world where, you know, investors want to access China, but they require interlocutors to which to do it. So I understand the argument that China of course has, you know, like interest in boosting Shanghai of Guangzou or Hainan island. Some of their latest measures are really focused on Hainan, which is really interesting. Maybe that's the next, you know, kind of a city state. But, you know, it's, it's, it remains to be seen what happens to Hong Kong. And I think the human capital aspect of this is, is really, really relevant. I don't think that city-states are possible without human capital, and that's what Singapore got right really well. Aaron Watson: Right on. I could probably talk about these different types of places with you forever. But I do want to spend some time because this is a show that it's categorized as a careers one, and how you found yourself in this role with the Clocktower Group. You're very candid in the book about how you were going down the conventional PhD professorship type of track, and then have taken all sorts of different diversions. I wanted to start basically, just talking about your time at Stratfor and explaining for a little bit about people, what Stratfor is was, and how you kind of found yourself there. Marko Papic: Yeah, so Stratfor is in the political risk industry. Just like you raise your group as well. And so when I got disillusioned with academia and said, well, I should probably learn how to, you know, I should probably have a real job at some point before I decide to go into academia. It was just obvious. It just made a lot of sense. And so I joined it. This industry is not that big, you know, that's, what's interesting about it. It's it's actually really small. And so, you know, getting a foothold in, in the kind of a political risk space, it's much more difficult than people think. And so it doesn't really exist as a profession. And so I was very fortunate to be able to, you know, spend some time at Stratfor, and, and learn some of the ins and outs of how one actually, you know does political risk analysis. And what I found while I was there was that it was kind of useful for a lot of CEO's and a lot of corporates as a background, but I didn't feel like it was really you know, it was nice to have, not a need to have, the political kind of analysis that we were doing. And I felt that there was a way to do it in a way where it could actually generate alpha. That's the name of the book, which is returns above a certain benchmark in finance. I felt that there was actually a way to use political analysis to beat the markets in certain, you know, cases. And so that's why I decided to cross over more specifically into finance. But I definitely get a lot of questions all the time from people in LinkedIn or young people studying international relations and political science, like, "Hey, how do you actually enter this industry?" Aaron Watson: And yeah, you mentioned it being such a small world. I didn't even quite realize it. I first saw one of your interviews on RealVision, but you know, the Stratford that's where Peter Zion's come out of George Friedman. It seems like an exceptionally, a small circle of characters that you know, have the ears of those decision makers and have done the work to kind of prove that they can make a call. You can have some confidence in it know that it's it's well researched. One of the other parts that was interesting to me in the intro was I, I believe it was your partner there, the Clocktower group, Steven, who said that you were this nihilist. You had this nihilistic approach to analysis and in different interviews, we've kind of talked about that in, in, in a different context, not in geopolitics is potentially being harmful, but can you talk about how general nihilism about geopolitical analysis has behooved you in this profession? Marko Papic: Yeah. And I think that's the, if I, if there's one thing that I would take from the book and proselytize, it's that we need more, nihilists. Now not in your behavior as a human being, but in your profession. Why? Well, even if you're running an NGO and it's trying to fundamentally change the world, you can't be blind through the constraints that face you, you know, and in fact, I think the way to be successful in any endeavor that has to do with the real world, which is messy and doesn't obey Newtonian physics. And so you can't just outsmart it through math. So whenever you're dealing with societies or humans, I think it's really important to separate the analysis from your action and agents. And so I talk a lot about this. I call it a loop in difference, my partner, Steve calls it nihilism, and I mean, I do too, but the idea behind it is that in order to forecast where the world is going, you need to really wash away all the biases that you have. And that's a really difficult thing to do. And very few places will teach you how to do that. And once you do that, once you can kind of forecast where the world is going indifference to, whether that's good or bad, you know, putting passion aside only then can you actually figure out, well, how do I change that? But if you go into the analysis already biased or already focused on changing the world, you're just going to fail in my view. And you see this a lot, you see this in politics all the time. You have the zealots. Yeah. illogically committed zealots who basically come in and say, this is how we're going to do it. And they faced oposition because obviously they do .Now from their own personal self-interest and many of them want. They admit this they're really not trying to change the world. They're just trying to make themselves feel better by kind of washing themselves with their own preconceived biases and views. But if you want to change the world, you have to understand the constraints you're operating inside and then try to change those. But that, that starting point of a loop in difference, I think, is most critical in this analysis or really in any endeavor that has to do with, you know, human agency. Now the reason this is very difficult to acquire is because while we're humans and we're biased. But the second reason is that again, the political risk industry is very, very small. So most people who've been international relations or political science, or are interested in this. They either go into government, you know, we're obviously they don't get trained in nihilism. We'll loop in different. I think it'd be, I think they should be, you know but they don't. Or they go and go into kind of the international organization NGO world, whereas you definitely don't get instructed on this method. Or you go into business or you're in finance where you would think where you would think that people are instructed in how to think analytically and separate themselves and their own views from their analysis, but they actually don't. And so there's still this kind of indignance and just kind of you know judgmental quality, even in finance to viewing the markets as right or wrong, or what policymakers are doing is stupid. You know, things like that. Then, you know, you get faced with this, even if finance where it's like, it's not stupid, it's just is, so act accordingly. And I think that it's very difficult to train this. How do you train it? I think the way you train it is you try to use empathy a lot in your analysis, and you try to put yourself in the shoes of those who you even really disagree with. This is really critical. To becoming desensitized to yourself and to be able to start looking at concrete data and objective facts in forecasting where the world was going. That's where it starts. Aaron Watson: Well, it sounds like you are though optimistic about the ability to train someone towards that because I would, I would struggle almost with differentiating, you know, the right team culture, where leaders and the, the norms have been set, that we're all gonna, you know, point out each other's biases and kind of correct when someone's being too ideological and a view that would be one kind of arena where you can hopefully develop other people to operate that way. But then there's also like my mind goes to almost just like, you know, they have a different kind of psychological personality profiles and someone that just is oriented around disagreeableness is going to be much less likely to land in an environment where everyone's kind of nodding along. So if you kind of have that, that disagreeableness off the bat, you're more comfortable being like, well, that's a ridiculous tape that doesn't have any sort of grounding and the actual facts on the ground. Marko Papic: I'm not sure if it matters if you're disagreeable or not, you know, maybe even make an argument that disagreeable people are more likely to have a counterintuitive view. Like I think it comes down to this. I mean, I've, I've worked with disagreeable people and agreeable people who both equally were unwilling to think outside the box. It requires several things. I think, one, it requires you to have, at some point in your life, been the other. I do think you cannot do this without it is extremely difficult to have a level of aloof indifference that's required for forecasting the future without having been othered at some point. Whether that means that you grew up in Arkansas and then you will land in Manhattan. Like that's good enough for me. I'm not asking for you to live abroad or something like that, but you have to have sometimes been out of, like, out of place. Because that act of sort of cultural and social, social, you know, otherness gives you the necessary level of a now analytical capability to then understand that everything is relative and how somebody can act under constraints in a certain way. I think that's, that's like the starting point. You have to have felt that at some point, or maybe you were born just different, you know, you're, you're a kid in a family full of football fans. You're like you're rebelled and you're like ice hockey. Like that's good enough for me, you know, but the point is that at some point you'd like, you have to have felt that. Once that's done, then you have to kind of seek it out because the, the critical point of analyzing societies and then making a difference is being able to forecast correctly, policymaker moves without thinking that they're stupid or that they're driven by this or that. You know, once you're there, you can then focus on the objective facts. And that's why I keep saying, like, even if you're running an NGO, that's, you know, focused on climate change, even if you're, even if you're extremely like focused on normative and value-driven issues, you can still be pretty nihilist in your analysis right up until the point where you then have to act on your analysis of how to change the world. Aaron Watson: Right on. Well, my last question before we ask our standard ones for wrapping up is precisely the opposite of nihilism. You mentioned being a basketball fan, a soccer fan as well. Where do your fandoms lie and what are your expectations for the 20 21 NBA season? Marko Papic: Well, I'm a huge Laker fan. I had this before I could speak English growing up in Serbia, huge basketball fan. And so I think, you know, The Lakers will probably win again. I guess I'm hopeful of that, but but you know, it's, it's a great season and it could go either way. That's that's what's interesting about this. We'll see. Okay. Aaron Watson: Yeah. If we get a, a, another Katie-LeBron showdown in the finals, that would be absolutely stunning. Marko Papic: Right? That will be awesome. I think, I think that would be really good. Aaron Watson: Cool. Well, before we ask the, in the last few questions, Marco, anything else you were hoping to share today that I just didn't give you a chance to? Marko Papic: I guess you know, one thing I would say, just in terms of this, this industry political risk industry I do want to spend maybe just a little bit more time on that because I do think it's a growing industry. I just think that a lot of people who tried to get into it go about it the wrong way. And the reason I say that is that, you know, they see someone like Ian Bremmer or someone like George Friedman or Peter Zeihan or myself. And they say like, "Oh, I want to do that." But the issue is that you're looking at the end of the line, you know, like you're looking at the end of the assembly line and what you should be thinking is how do I enter the assembly line? And the only way to really enter the industry of political or geopolitical risk analysis is to become an expert on something pretty small. Don't think big picture, you know, don't try to become a global strategist on day one gain an expertise, especially in parts of the world that are not. You know, interesting right now. So you know, like learning Mandarin in 2021 is the wrong time. You know, if you're an American student, you know, it'd be like learning like Arabic in 2011, like bad time to do that. So start thinking about, you know, where the world is going, what matters. For example, climate change is something that I think is a really big issue. I think that policy makers are reacting to it. And I think that that's going to require a level of investment in commodities that we haven't really seen in awhile. And we're starting suddenly going to start caring about things like nickel or cobalt or lithium, and guess what the good news for someone who's young is that a lot of these things are found in places that no one's really spent any time studying for a very long time. So if you're interested in Latin America or Africa, I think that your time will come. And so, you know, Focus on developing an expertise in a skillset, in something that's digestible that you can study. And from there, you can eventually become, you know, someone who has a global purview. But thinking that you're going to start off with a global perspective, you know, right out of university or right after a master's even is just, it's not feasible. It's not realistic. I mean, as I write in the book, I started off as a European analyst, which was about as interesting as being an Admiral of a Swiss Navy know, always make fun of myself for that, but it ended up being really fortuitous. I got lucky that the EU crisis hit, but I developed a competency in something that nobody else really wants to touch to be quite Frank with you. So I, that would be my advice for a lot of people trying to get into this field, find a niche and the niche doesn't have to be a geographic. It doesn't require language study necessarily all the time. It might be something in, you know in technology that's emerging, it might be something in a policy that's emerging. That's cross-regional cross-country but focus on developing an expertise first and then thinking about branching out to more regional and global issues. Aaron Watson: I love it. We've hit on focus twice. It's one of the most important ideas. Marko, if folks want to learn more about all the work that you're doing we're going to link to the book in the show notes for people, if they want to check that out, but any other digital coordinates that you want to provide for folks that want to learn more? Marko Papic: No, I actually don't have any. If I had any advice, it would be stop listening to people like me. There's this, you know, like there's this huge obsession would following the right people. Ultimately anything that you get from me in the, in the sort of ether of the internet, is going to be not really that useful to be, to be quite honest with you. I think. Focus on learning from yourself. And I think my book was written specifically to empower, you know, mainly investors, but it can be anyone with this idea that you yourself can do the hard work. So I actually am not available anywhere outside of the book all the research that I produced is really for a select group of institutional investors. And so, yeah, I mean, and, and what I would say is like, you know, maybe whatever, however many people you're following, cut it in half and do more deep reading and deep analysis yourself. Aaron Watson: I take that. Can you talk about some of the sources that you go back to most frequently when you're trying to get to that ground truth? Marko Papic: Yeah, that's a great question. Always primary, primary, primary, primary, primary, primary documents. Always! I don't know what they teach history classes, but it's not how to go to the primary document. Like I can tell, you know, like this is key. This is key. You cannot go to a blog post. You cannot go to New York Times. You cannot go to Financial Times. It's not research. It's just not. You know, it's entertainment first and foremost. The only place where you can find true truth is the primary document. So if you are trying to figure out what's going to happen with the fiscal stimulus in the United States of America, don't go and read what New York Times says about it or Axios or Politico or The Hill. Although those are especially The Hill, very good sources of information, you want to go and actually read them. And if you're starting out and, you know, like the reason I really love this podcast Aaron, and the reason I want to do it is because I do want to talk to young people trying to get us into in this industry. What I would say is like, read less of stuff that's easy to read. Read more of stuff that's really difficult to read. And you know, it's difficult to read? A bill! A c- c- congressional bill. A House or a Senate bill. Oh my God. It's one of the most boring things you can do in your life, but that's where you're going to start, you know, like, can you read like five of them, you're going to start seeing like interesting tidbits, interesting knowledge that other people have not picked up. And that's something that a lot of, of my mentors, like my partner here at Clocktower, Steve Drobny have said, I mean like, you know, the median person you're competing with is lazy and they're not going to do the hard work of going through the primary documents. And so put in the effort to do it. So how do you collect information? How do you become more aware of what's going on in the world? I would say there's like, there's three levels. One is read the news you know, just headlines. I prefer to use Reuters for that or the wire services, like a AFP or AP, like the, the less analysis there is in the news, the more I liked it. I don't need someone to pre digest the news for me and give it to me a little slices. I just want the actual thing that happened. So that's first. The second is talk to people. Get a group of friends that you really admire. Get people who can, you know, where you can talk out ideas and what's going on in the world where you can have this iterative dialogue, because that's where you're going to get great ideas. So basically you get the news, you hear what happened, you run it through a filter of really important people that you admire. Hopefully some that are older, different perspectives, more experienced, whatever the case is, then you come up with ideas and you pursue those ideas by doing deep, deep knowledge and deep analysis in deep breathing. That means academic papers. It means books, and it means primary sources. When you read academic papers and when you read books, read the footnotes. Occasionally there'll be funny if you read my book, for example, there'll be many in there that are funny and some that are not. Why do I have funny footnotes? Because I want you to hope that every footnote is worth reading. And most of them are because that's how you get to other sources of information. Some of the best thinking that I've done in my life, in some of the things that have made my career were found in footnotes. Where you read an article about why an academic piece, about why issue Y and then you get to issue X because of that footnote, and it blows your mind. So that's what I would say. I mean, the questions that you are posing, Aaron I get it a lot. What do you read? And my answer is I don't read anything that can really be read very quickly. I don't read any of the things that you would expect, like the economist, foreign affairs, foreign policy, all that stuff is not useful. I think obviously if you are, you know, building a company, that's doing something specific where you don't have to be a geopolitical risk strategist, right? Definitely. You should read the economist. Like that's my favorite. Like for sure if it's just something you want to have on your mind, that makes sense. But if you want to do this professionally, what I'm doing, this is the only way to do it. Aaron Watson: I dig that. Well, part, part of my game is to try to get around really smart people. And I'm not afraid to say something that's probably not correct and let them correct me on it. That's one of the ways I like to go to the source as well. But I I really, really appreciate you taking so much time to talk with me and share your stuff with the audience. I prepped you for the challenge at the end. I feel like we got a couple here. So if there's still another challenge that you want to shoot the audience this is your chance on the mic. Marko Papic: Yes, definitely. So my whole thing is the hardest part about this job, the toughest part of this job is to really try to be as, as unbiased as possible. And I've tried to do that in my life by surrounding myself, by people who I disagree with, you know, On on some important issues. Although I don't have anyone in my life was a Clipper fan and I never will, no, I'm not. No, but so what does that mean? What's the challenge? Well, I think there's two parts of the challenge. I think one is trying to do what I said and I mean, this is, this is so important, whether you are, you know, hoping to have a geopolitical risk kind of analysis career or finance career or not. But I think spending time abroad is really useful. And I know that's been said before, and I'm sure I'm probably not the first or the last, who will say that as a challenge. But I would say that right now, I mean, this summer is a really good time. Spend some time abroad. If you were at a university, do it for sure. Like, this is probably the most useful thing you can do at the university. The second thing I would say is, you know, if that's, it's like too big, like I can't do that tomorrow or this weekend then do something different. You don't like go to a, like a political meeting. Or go and talk to someone who is on the exact opposite political spectrum from you and spend some time to listen to that. And don't really just ask questions, you know, like spend like as much time as you can just listening. And if you can't find anyone, which would be really sad, if you can't then just watch the TV channel you deeply disagree with for like a week, make it like almost like a medicine you take before you go to sleep every night. And the reason I say that is because you really need to learn. I think in life, you put yourself in the shoes of those who think differently and act differently than you, because that act in of itself will make you a much better analyst. I mean, that's that, that's kind of the core. I mean, my book has a bunch of pants, examples of finance and all this stuff, but fundamentally speaking, if you're going to be in the industry of analyzing politics or geopolitics for living. You have to be able to have a baseline level that's analytical and in order to produce outcomes and produce forecasts, then you can, you know, what you do with that is obviously what you want. You can change the world with that. You can be extremely non nihilist with it, but the analysis itself has to be done from that baseline level of a loop difference. And it's impossible to do that unless you practice. Aaron Watson: Right on. Well, hopefully many listeners will take the challenge, practice it and have a bunch more nihilists walking around. Marko Papic: Well no! Not necessarily nihilists. Just analytical nihilists. But then what you do with that - please I'm not trying to say... Aaron Watson: Yeah, yeah, yeah, I'm just joshing you. Marco, this has been great. Thank you so much for coming on the show. Marko Papic: Okay. Awesome. Thank you for the opportunity, Aaron. And I hope that you know, I hope it was helpful. Aaron Watson: It absolutely was. We just went deep with Marco Papic. Hope everyone out there has a fantastic day.

1 Comment

4/11/2022 06:25:09 am

Most of the time I don’t make comments on websites, but I'd like to say that this article really forced me to do so. Really nice post!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Show NotesFind links and information referenced in each episode. Archives

August 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed