|

Steve Muck is the CEO of Brayman Construction, a heavy civil and geotechnical contractor that builds bridges, dams, and other large infrastructure. Steve is also the cofounder of construction-related robotics startups TyBot and Advanced Construction Robotics.

Steve has started or acquired twenty businesses and currently operates a portfolio of entities that in construction-related endeavors alone runs approximately $200 million in revenue annually. Steve acquired the company over 28 years ago in a leveraged buyout and has since acquired a number of companies as he has expanded his business empire. In this episode, Steve and Aaron discuss how Steve got started in construction, the company’s ‘Dragon Slayer’ ethos, and how he has upskilled his team in order to escape competition. Sign up for a Weekly Email that will Expand Your Mind. Stephen Muck’s Challenge; Take a risk. Connect with Stephen Muck

Linkedin

Brayman Construction Website If you liked this interview, check out episode 412 with Jake Loosararian where we discuss industrial robotics and raising one of Pittsburgh’s biggest Series A financings. Text Me What You Think of This Episode 412-278-7680

Muck: The trade unions that we interact with the laborers and the ironworkers. When we introduce the products to them, and we started talking about what we were doing, they actually embraced Thai baht because they've had customers like me coming to them, looking for people in the peak season and they don't have them. And it's very frustrating for them to have to tell me as an employer or a customer that we can't send you a five guys cause we just don't have them.

Watson: Hey, this is a very special episode of going deeper with Aaron Watson, my guest, Stephen Muck has taken a company that he acquired over 28 years ago. That was doing $7 million in annual revenue and built it into a multi-faceted diverse powerhouse. Doing more than $200 million in annual revenue. Stephen talks about how he's built the business, the role that robotics and automation will play in the future of construction, and why he trains all of his executives to be dragon slayers. There's a ton here. We didn't have a ton of time with Stephen. So I tried to move it at a really quick pace and think you're going to take a lot away from it. Here is Steven Muck. Watson: Steve, thanks for coming on the podcast. I'm excited to be talking with you. Muck: Yeah, it's my pleasure. Happy to be here. Watson: So I'm going to go back to 1992, you had started your career in investment banking and made the decision to acquire a construction company. How did you make that choice? And can you talk a little bit about the state of that company when you were acquiring it. Muck: Sure. Let me take you back one step further. Watson: Okay. Muck: Okay. Because I think it's relevant and it's maybe a little bit interesting. So when I got out of school undergrad, the first job I took was in economic development. So I actually worked for private, nonprofit corporations doing job creation, economic development, creating small business incubators, assisting companies with developing business plans and funding them using public funding programs to supplement bank funding. So, that was really unique environment because I had sort of the who's who of various communities on my boards. And so those board members became mentors to me in various ways and had a lot of diverse business background. So when I left investment banking to acquire my first business, Braman construction was a little $7 million rusty construction business that was focused on doing subcontracted, concrete structure work for, the bigger earth movers and things of that nature. So that's kind of where they were when I came on the scene, they had some older superintendents, they had a lot of older equipment. And I was full of piss and vinegar, and ready to rock and roll in and figure out a business that I really didn't know much about. Watson: And so for folks that are less familiar with contracting generally, subcontractor general contractor, that's relatively self evident, but in terms of the stair-step up, this is how I was thinking about it coming into the interview. And you just correct me if I'm wrong, a subcontractor. It is somewhat constrained and is relatively, I mean, maybe you're just absolutely world-class in that little sub domain, but there's a lot of competition, a lot of different electricians, carpenters, plumbers that could potentially bid on the general contractors job. And so, first by climbing up into being a general contractor instead of a sub, and then moving into the different specialties that Raymond has developed underwater, efforts, bridges, dams, these really kind of complex, heavy civil infrastructure projects. It was really a study in differentiation and kind of escaping a lot of the competition in the construction realm. Muck: Yeah. That's fairly accurate. I mean, as a subcontractor, you need your horse to win the race, and then you need to be the jockey that got the ride. So, that it, your odds, aren't the greatest. And as a general contractor, you have much more control of your own destiny. So we work in both hard bid and negotiated environments. Most of what we work in are hard bid environments, which means, if you're qualified and you're low, you get the job, which means you have to be efficient, you've gotta be good at what you do. And as a subcontractor, you don't have that luxury. You've got to have a relationship with that general contractor and that general contractor has to be successful. And then ultimately has to select you to do the work for them. Watson: And so what is the muscle or kind of experience that gets built to be able to consistently land in those in low bid environments, because, you could, you can't necessarily forsake safety or kind of basic like cost of goods sold, or things like that. Where is the competitive edge that allows a company like Braman to win those qualified and low bid type of situations? Muck: Yeah. It's really experienced people. We're margin hunters, so we built the business on hunting margin, making money, reinvesting that capital in our business, in our business plan and in our target markets. So we've had to make the money to be able to grow the business and to do that. We kind of focused on higher profit activities and the higher profit activities tend to be riskier in a number of different ways. And you're absolutely right. We keep safety first in everything we do. So you can't soft sell safety in anything that we're doing. And frankly, over the years, we've learned, I've learned that having a safety first environment creates a more productive workforce. They feel secure, they feel safe, they know that we're looking out for them and we expect them to look out for each other. They tend to be more productive. So, to find the margin, you have to rub up against the risk, and a lot of our businesses are risky businesses. Our foundation business is risky and that you don't know what the subsurface conditions are, and you may have soil borings that give you some indications, but it's not crystal clear. So, that's a risky business. To the extent that we've learned to develop ways of solving problems in that environment, it lets us mitigate the risks. Maybe more effectively than other contractors, which let us embrace the challenging work, which is really twofold. It creates organizational development and it creates the human development in your people by providing them with unique, interesting challenges, and at the same time we still do mundane sort of straightforward projects, but we're always out looking for things that haven't been done before. Watson: And so that was kinda the next question I was thinking about where, Hannah and I run a media business. If we want to go run an experiment, we can make media for ourselves. And there's, it takes some time, but there's not some sort of, kind of physical output or outlay that has to be a prerequisite for that type of experimentation. You can't necessarily go just, Hey, we're just going to go build a bridge somewhere else way, way beyond the bounds of some of these possible. So as you try to move an organization in the direction of some of these riskier ventures, these potentially higher margin or less competitive ventures. What is the on-ramp? Is it recruiting the right person? Is it, what gives you the confidence to even say, hey, we can go fill that need that we put the bid in for something like that. Muck: Yeah. I think, institutionally it's having done it. Before when we started down this road, we were a little $7 million business. So we've, incrementally reached and reached and reached and grown and done more challenging, more interesting work. Another way we approach that is by combining the various expertise that we have. So, we have our Marine construction capability, we have foundation capabilities. If we combine those, it lets us go after a combination of let's call it a Marine foundation job, which is complex. And there are fewer people who are willing to, or capable of going after that work and having the confidence to know that they can get it done and they can get it done right. So it's having the right people. It's sometimes acquiring the right business that brings a certain new skill set to us. Sometimes it's hiring an individual, who's got a specialization in a special capability and bringing him into the team. And some of the things that are kind of fun and exciting for us is that we get people joining our team because of the diversity of things that we do. And good people want to keep learning and developing their skillsets and working with people who can help them. And we've got a, an interesting mix of young folks and some older folks who've got great experience. And so, our young people turn tend to learn up pretty rapidly here in this world. Watson: Yeah. So in that spirit of the acquisitions that you've had in order to kind of assemble Braman into this company, one of the things that was really interesting to me is in startup culture, there's this celebration of equity sales in the forms of your series A or series B in it. And people are like, oh my gosh, congratulations. And what you actually did was just sell your equity off to these other kinds of outside investors. Was it, it was a leveraged buyout to, for acquire Braman. Can you talk about the financial construction side of the business? And as you do these acquisitions, is that mostly through debt financing? Is that something that because of your background in investment banking, you kind of had that legibility into how to best do that? Muck: Yeah, I mean, initially it was, and it was kind of interesting when I finished grad school and I was trying to decide what was next. The banking industry was kind of a nice place to go because ultimately I knew I wanted to be debt developing my own businesses and working for myself. So developing those financing skills and the banking experience really gave you a lot of credibility for that first deal in particular, because I knew what they wanted to see. I knew how they wanted it structured. I knew what was reasonable from a projection standpoint. So it did give me kind a basis for starting down that road. And then as we've gone, the deals are all a little bit different. But typically we've bought small businesses with a few good people in markets that we weren't currently in. So new products. So whether it was our large diameter drilling business, we acquired that was the first acquisition. That was a bankrupt company that was owned by, at that point, our bank, had taken them, had taken their assets and we went in and, bought the assets from the bank and went back and picked up some of the people that were cast offs from the bankruptcy and brought them back and started down that road. So back then, it was very much a bootstrapped diversification because we were still building profits, and building our equity. And we didn't have a lot to work with. So there was a lot of leveraging going on back in that day. Watson: Makes sense, and that's kind of opportunistic. It's a great deal. Maybe more so than like the perfect strategic compliment, but as you continue to grow, then you can kind of step back in. That really seems like what advanced construction robotics is, is much more of a stepping back, surveying the landscape and saying, this is something that needs to exist. And we're going to apply robotics to construction, which is, is relative to the other industry has been somewhat less automated than many of the other, Muck: Right. Yeah. That's a great point. And that's a great contrast, that first acquisition being a bankruptcy that was repoed by our financial institution, we bought the assets for dimes on a dollar kind of scenario, and got the business back on its feet. And then, with advanced construction robotics, it's, 25 plus years of watching the construction industry as a business person, more so than an engineer and looking at it and recognizing that our productivity is we're dropping, our workforce availability was becoming more and more of a problem. Safety had become more and more of a concern. And we started looking at which activities were repetitive and what the convergence of technology was at that point, which was about four years ago. And really came to the conclusion that the technology had reached a point where, as it was converging, it looked like there was an opportunity to develop solutions for the construction industry and the heavy civil marketplace. And that's really what started is we looked at it and said, somebody's got to do something and it's much better to develop solutions for problems than develop technology and then go looking for the things that it might do in a marketplace. So we very much focused on the problems in the industry. And then, ultimately I was very fortunate to find the right co-founder and build the right team of mechanical electrical motion control, vision, artificial intelligence, software guys, and pull them together with this vision to be the premier robotics solution provider for the construction industry. That's kind of, that's the position that we feel that we sit in right now is one of the very few entities who's actually developed and commercialized construction robotics solutions. Watson: And so when I, researching advanced construction robotics. My mind went to AWS and Amazon where AWS is cloud computing was first. Its first client was Amazon's retail business, that e-commerce website. And they were able to kind of sit side by side as a very amenable, friendly client to them as they built out the model, and then eventually that spins out and that's wildly more profitable than Amazon's e-commerce business. And it sounds very similar here where, because you're in the business of building bridges and you have the weight to say, hey, you're going to try this robot out of this job where there's probably some skepticism at first. And take qualitative feedback, see where the opportunity is and get that actual real life laboratory, as opposed to the theoretical laboratory in order to roll out that product. Muck: Yeah, that integration capability is one of ACR strengths, because of our ability to iterate quickly, and get direct input from the people with boots on the ground that are actually doing the work, we're able to cycle through our prototypes extremely quickly. We understand the parameters that we have to work to from a productivity improvement standpoint, to build a commercially viable product. And our mission is to embed the least amount of technology, necessary to create a robotic solution that has a robust economic impact. And that's really what our focus is. And we're moving on to our second robot now, and we're in prototype development there with full-size, and that next robot is called iron bot and it will carry in place rebar. So, another very labor intense, strenuous, activity that generates a fair number of injuries because of the need to walk on uneven surfaces, carrying weight, and do it in unison with four or five other people because the rebars long, and then you bend over and put it down and stand up, take a step and over and put it down. So there's a lot of repetition. So we're solving productivity issues. We're solving manpower availability issues, and we're solving safety issues all at the same time. Watson: Yeah. I was really curious if you could talk about like the messaging of something like this being implemented, because I know that the labor conversation is all over the place. I think literally this morning, the new labor numbers dropped of simultaneously more people, unemployed and more companies struggling to like find people to fill their roles. And that's something that the construction industry is not, it's no stranger to. So can you talk just in broad strokes about how you've managed that through your different construction entities, and when something like this gets rolled out and you, maybe when your guys it's like taking a sideways glance editor or more maybe having a harsh word, like what is the messaging coming from leadership in this type of environment? Muck: Yeah. It's interesting. There's, I mean, the construction industry. It is very slow to adopt new technology. There's a real desire to kind of do it the way we've always done it before, because we get an adequate result. And some of that comes from the fact that our products are engineered in significant detail because they're carrying traffic and there's human life type issues involved in safety issues. And so there's a reason for that, but there are also opportunities to adopt new technology and we're trying to push that forward. So, one of the really interesting things as we were introducing the robot was that the the trade unions that we interact with the laborers and the ironworkers, when we introduce the products to them, and we started talking about what we were doing, they actually embraced Thai baht, because they've had customers like me coming to them, looking for people in the peak season and they don't have them. And it's very frustrating for them to have to tell me as an employer or customer that we can't send you a five guys cause we just don't have them. So they looked at the robot as a solution for that labor scarcity. And when you drive it down to the individual level, the guys really don't like the work. I mean, it's strenuous, it's repetitive, it's boring. There are higher and better uses of skilled construction labor than doing these tedious, repetitive activities. So most of the manpower are happy to see these tools come into play. Now the nuance is if the construction industry is slow and I have some of my people sitting on the bench per se, so not actively employed in the workforce, then, I may let that technology set bring my people back to work first. And then once we run out of our skilled labor, then we go back and we say, okay, now we're going to use those robots. As the robots become more and more economically compelling. Hopefully the construction industry is picking up and, and busier. And so, we're happy to have those robotics solutions, but we have seen that ebb and flow and in a robust construction environment, we see a real poll for those solutions, in a very slow construction environment where maybe there's people, looking for work, then there's a little more hesitancy from the contractors and employers because they want to keep their steady people busy first. And we get that cause we live in that world. So we have seen those kinds of nuances. Watson: So do you see from your vantage point, those type of labor shortages, and we've talked about something similar without one of the third-party logistics providers about the kind of shortage or the trouble with retention for truck drivers and some of these industries. Do you see that as like, if there were the kind of different variables, the just kind of way a generation was raised, everyone was like center sent to college in certain ways. Blue collar work was like disrespected, and in certain educational circles, you see that as a demographics thing. Do you see that? Like how do you try to piece apart the why behind those types of shortages or is it just cyclical? And it's like this macro cycle is in a high build versus a low built type of state. There’s gonna be $2 trillion infrastructure bill or something like that. Muck: Yeah, no. I think traditionally, we've assigned certain stigmas to working with your hands. As a society, at least in the US, and probably in most of the developed countries. And we've pushed kids towards higher education. I think there's a real opportunity right now from a trade skill standpoint. I mean, we have guys working with their hands, making six figures and doing very well. I see other young people come out of college with degrees and they're having a hard time finding a job and a fair amount of time and a fair amount of debt. Right. So, I mean, I really think that as an industry, we need to do a better job of kind of sharing the opportunities. I described the construction industry as the last bastion of the wild, wild west. And what do I mean by that? Well, we're an environment where, if you're a good gunslinger and you're willing, really willing to work hard, and you're a young person, you can get ahead. Very rapidly in this construction marketplace, it's a matter of really putting your heart and soul into it and applying yourself, but there's so much opportunity. I’ve got three or four people running profit centers that are in their mid thirties, and some of them started in those roles in their early thirties, and I guess it's become sort of one of my philosophies because when I did do my first leverage buyout, I was 31. So I don't discriminate against 31 year olds running businesses. As a matter of fact, one of our philosophies here is, we like to teach our young people, not just the work that we do, but the business we're in. So how the business works, the upside with that as we get some very energized and involved young people who not only understand how to build construction projects, but actually understand the way the levers push and pull to make the business grow and develop and how we generate profits and, and how we plan for the future. Watson: And ultimately, you said you started as a $7 million business when, at least from what LinkedIn said over 200 million in annual revenue now, and the only way you scale to something like that is by developing people that can make good decisions on your behalf. You have only so many hours in the day. So many brain cells, you can't make every decision. And so, it’s only through that legibility into the org and how it functions that those people are going to be trusted to make those types of goods. Muck: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, that's one of the things I joke about. I've got a lot of people running around with my wallet, and my credit card and the message I give them is spend it like it's your money, treat it like it's your own, and we'll never get sideways. Just when you make decisions to why you're making it and have good thought process. Get good feedback and go get it done. Watson: Right on. Well, I wanna be respectful of your time. We'll ask our kind of last wrap up questions here in a second. But before I do that, I've got one question that did not plan on asking until I entered this room that we're seated. Can you explain what a dragon Slayer is and how important that is to your org? Muck: Oh, that's colorful. So, it comes from me sitting around our construction meetings. At the end, I used to tell the guys still do to go slay dragons, which simply means go do the difficult things that you need to. So the dragon slayers have evolved into our senior management team and the thought process behind them is they're standing back to back in a circle with their swords out towards the dragons or the enemies or the challenges of any day, week, year. And inside that circle is our corporate family. So all of our people, our employees’ kids, our employees’ spouses, all the college tuition payments, all the car payments, all the mortgages, and our mission is as senior managers are to protect and grow the business and take care of that society. So, it's a little bit gothic, maybe. But it's really about the other saying that we have here, that you may have seen somewhere on the wall is we, what we killed. So the saying there is simply to call out to our people that we live and work in a very competitive world. And it's either our lunch or it's somebody else's lunch. And we have friends in the industry, but at the end of the day, we’re in a competition. And so I like for them to have that in the back of their mind and recognize that edge, that there's winners and losers and we're in a competitive world, so let's get after it. Watson: Beautiful. Well, hopefully the winds can continue to keep piling up and the team continues to grow. Before we ask our standard last two questions that I prepped you for, Steve. Anything else you were hoping to share that I didn't give you a chance to? Muck: No, I think you've asked great leading questions and we've really covered a lot of it. You've clearly pulled out our tradition of heavy civil construction projects and, tied in my interest in technology and driving technology into the construction world and marketplace. That's a real passion of mine. So I'm happy to have got the opportunity to share that. Watson: Beautiful. Well, hopefully we can do this again sometime, and I can learn more about building a business empire and building a dam and all these other cool things that you've been up to. But, for folks that want to learn more about Braman, about you, the different things that you do, what digital corners can we point people towards? Muck: Yeah, I mean, I would just point them at our website, at braman.com and at ACR bots, to follow both the high-tech part of our business and the core construction elements. Through those websites, they'll find links to the various companies that we have and the businesses we're in. Watson: Beautiful. We're going to link that in the show notes. For this episode, you can find it in the app. We are probably listening to this or going deep in with Aaron dot com/podcast for every single episode of the show. Before I let you go, Steve, I'd like to give you the mic a final time to issue an actionable personal challenge for the audience. Muck: Hm. Okay. Actionable, personal challenge. Take a look, take a risk, and put it out there and go after your dreams. Watson: I took it. Can you tell me about when you made that decision to do the leveraged buyout of Braman and whatever the perception of risk was at that point in time? Can you just talk through, like how you navigated that? Was there a point at which you were unsure if it would occur or if it would be capable to come through? Like what, like when you were at the riskiest point, what was the kind of mental self-talk that got you through that situation? Muck: Yeah, I think, any deal you do has points at which you think you may or may not get it done. So I think that the concern was that I had a really great job. I was doing a strategy for nations bank. So I was buying banks and assets for the bank reporting to an EVP who reported to the CFO who reported the chairman. So I was basically four seats away from the chairman and I would get calls occasionally from the chairman asking about different deals we were working on. So a super cool job that I walked away from and they were a little stunned when I did. So I guess I was concerned about making sure that I was doing a good job for them while I was working on this deal, and the deal was pretty personal and pretty consuming. And so it was my job. So balancing those two, was probably the biggest challenge, I think. Because I wanted to make sure I was doing the right thing for my current employer. And I was very passionate about what we were doing and the deals we were working on. Watson: Right on. I love the side hustle. That's another, a consistent theme throughout the different interviews that we've done. I really appreciate you taking the time to be on the show. Like I said, I hope we can do it again, and appreciate you giving us some of your time. Muck: Yeah, absolutely. My pleasure. Watson: We just went deep with Stephen Muck. Open out there has a fantastic day. Hey, thank you so much for listening to the end of my interview with Steven. If you were interested in our conversation about how robotics can impact heavy industry, move people out of dangerous work and fill gaps in labor shortage. I think you'll also enjoy our conversation with Jake Luciferian from gecko robotics. His company builds robots that inspect large energy infrastructure, keeping humans out of dangers, arenas and making the inspection process simultaneously more thorough and more efficient. He talks about that in the interview. Go check it out. It's linked in the show notes and hit subscribe because we've got a bunch of great interviews coming down the pipe. Thanks for listening. Connect with Erin on Twitter and Instagram at Aaron Watson, 59.

2 Comments

Jon Pastor is the SVP for Consumer Solutions at RealPage, a leading global provider of software and data analytics to the real estate industry. RealPage was trading publicly at over $10 billion market capitalization before being taken private by Thoma Bravo.

Jon’s entrepreneurial career started when he cofounder RentJungle with previous guest Geng Wang. That company was acquired in 2014 and Jon chose to stay on and lead the acquiring company as President. Four years later, that company was acquired by RealPage. In this conversation, Jon and Aaron discuss the lessons from all these acquisitions, the challenges facing the real estate industry, and the incentives that guide successful organizations. Sign up for a Weekly Email that will Expand Your Mind. Jon Pastor’s Challenge; Create a list of ideas for projects or businesses that you could start. Connect with Jon Pastor

Linkedin

Website If you liked this interview, check out episode 474 with Geng Wang where we discuss three startups, social enterprise, and where to find motivation. Text Me What You Think of This Episode 412-278-7680

Jorge Mazal is the Chief Product Officer for Duolingo. Duolingo is a free language-learning website and mobile app with over 500 million downloads, 40 million monthly active users, and a valuation over $1 billion.

Jorge previously worked on the product for Zynga, MyFitnessPal, and Kleiner Perkins. Today he blends skills in design, gamification, and leadership to manage a product team that has 10xed in size since he joined the company. In this episode, Jorge and Aaron discuss how Duolingo makes product decisions, the importance of interpersonal skills, and how Jorge’s background has prepared him to excel in this role. Sign up for a Weekly Email that will Expand Your Mind. Jorge Mazal’s Challenge; Find some time to go help someone, with no expectation of anything in return. Connect with Jorge Mazal

Linkedin

Duolingo Website If you liked this interview, check out our conversation with Jason Wolfe where we discuss tech products, leadership, and entrepreneurship. Text Me What You Think of This Episode 412-278-7680

Underwritten by Piper Creative

Piper Creative makes creating podcasts, vlogs, and videos easy. How? Click here and Learn more. We work with Fortune 500s, medium-sized companies, and entrepreneurs. Follow Piper as we grow YouTube Subscribe on iTunes | Stitcher | Overcast | Spotify Watson: So thanks for coming on the podcast, man, I'm really excited to be talking with you. Mazal: Thank you, Aaron. Thank you for having me. I'm excited to be here with you. Watson: So I want to start off. I have to imagine that almost everyone that might be listening to this is aware of what Duolingo is. But maybe we can just start off, you know, this is an app with over fifth, I'm sorry, 500 million downloads, 40 million monthly active users, that has taught just loads of people, how to speak all sorts of different languages. Can you talk a little bit more just about what the apps mission is oriented around and the role that you play as chief product officer? Mazal: Sure. Yeah. So what the app does, is it's just languages and you can basically pick up Duolingo and just, even if he's just used Duolingo to learn a language, you can replace up to four, maybe even five semesters worth of college credit, worth of language education, which we're super proud of. And the reason why we do that. Well, we teach languages -- there are actually several reasons. We're a very mission-driven company. So we care a lot about the impact that language learning has on the world. And the truth is that the impact is different depending on who you are. So for a lot of people learning English, It's very transformational so they can access better jobs, better educational opportunities. And that's kind of, my lived experience has been bad. And also Luis, the CEO, has a similar life experience as well. And then also for a lot of people who maybe already know English, learning another language helps them connect with the world better. We have lots of users who are learning a language because that's the language that their in-laws speak, or maybe they want to learn Japanese so they can read manga in Japanese, or learn Korean to listen to K-pop or something. So there's this many reasons why people learn a language and we're excited to support all of those reasons. Watson: Yeah. I mean, those are exactly the two things I was just thinking about before we hopped on was number one, economic opportunity. We actually at Piper just hired our first international team member who just blew me away with his proficiency in English, despite that not being his native tongue. And that is, you know, part of how things get done. You need to be able to communicate, but at the same sense, you travel different places. And obviously that's usually--if it's a tourism related type of company-- that's part of the job, is to be able to bring people in and have that multi-lingual skillset. But it's also a way to connect. You know, there's a difference in walking through Tokyo and reading the signs in Japanese versus having someone translate it to you. You're getting that kind of layer of distance before you can really connect with the place. Mazal: Absolutely. Yeah. I mean, it's impossible to have an authentic experience when you travel unless you know some of the language at least. Watson: A hundred percent. So I'm super curious to learn more about the role of chief product officer. And later on, we'll talk kind of about how you've built up your skills and experiences to land in such a cool position. But, I guess maybe as a starting point, I think that, you know other roles, I think it's very legible how one is evaluated as an executive. So if you're a chief revenue officer, you need revenue to go up, right. If you've got maybe like a head of HR, it's are we hiring adequately? Do we have the kind of diverse team that we're pursuing with product that there seems like so many different kinds of lanes and avenues that it can go down. Particularly for something like we said, over 500 million, half a billion downloads of the app, all these different languages being taught. You could be, and I'm not saying this is the case, but just as an example, you could be killing it at teaching people Turkish. And maybe it's not as effective at teaching people French or whatever the thing may be. So how are you as a chief product officer evaluated, and then maybe we can connect that to how you actually spend your day in order to accomplish those goals. Mazal: Yeah. I mean the, the role of chief product officer, I think it's not standardized. I think it means different things in different companies. And at Duolingo, what that means is I lead three functions, which are product management, data science, which is kind of like early advanced, sophisticated product analytics that we do here and also UX research. So understanding our users and what makes them tick and all of these functions together are focused on really driving product market fit and constantly improving that fit. And also we know what's unique about Duolingo, and we have founders that are very technical, very product minded. So, you know, they're very involved in product, especially the recent CEO. And it's a very collaborative kind of way to make decisions with him, with chief designer, with our SVP of engineering, Natalie. So basically all of us together and our teams come up with a roadmap. Right. And execute on that in terms of, how am I evaluated in terms of performance? I swear it's different each time I get it back evaluated, it just depends on what matters at the time. Right. So, there's basically everything matters and whatever is not working well. That's the thing I need to be focusing, you know, next. So it's a matter of how well the business metrics start doing, and we care about, you know, user growth. We care about revenue growth and we care about teaching better. So we're always doing those three things. And at this point we're lucky that all those things are going really well. And we're just getting better and better at those things. And then there's also all of the people's side. Are we hiring the right people? Are they happy? Are they growing? And are they working well with others and creating the culture that we want? So, as my job has evolved, when I joined Duolingo, I came in as director of product and it was a very small team and that team has grown almost 10 X than it used to be. And so now a lot of my focus is on ultra, and how they make sure that people have the guidelines, have the principals, have the tools, the support system, so they can be increasingly more and more autonomous and more effective on, us teams. Watson: Yeah, I think we, in the pre-interview we talked to, when you joined, it was like 90 people and now it's over 500 people on the team. Mazal: Part of the whole company. Yes. Watson: Yeah. Crazy. So I was trying to guess, like some of those metrics, we referenced the monthly active users. And I guess the reason it's such a kind of moving target and those metrics changes, you know, something that maybe conventionally people understand for a Tik Tok or a Facebook or some of these other super apps that are at the top of the charts, because they are advertising based, more time on the app going from 30 to 40 minutes on average--it's time, someone spends on the app-- is really impactful because that increases the ad load that they can be shown. But at the same time, if you're also evaluating like the efficacy of people continuing to come back, you know, if it becomes this thing that eats up more and more of their day, maybe their kind of consistent habit of actually going and even making a daily practice of learning the new language is at odds with that. So that's a kind of a really interesting tension to kind of be playing with as a product lead. Mazal: Yeah. There's always a lot of different tensions and between the metrics that we care about, right. You could do something that helps with revenue, but hurts retention. You can do something that helps retention, but hurts the number of minutes per day they spend on the app and then those learning, going to the mix as well. So the way we balance that is we have teams that are -- some teams that are kind of metrics driven and they have like a goal to optimize revenue, for example, and that's the target metric revenue. And then we have guard rail metrics, which tend to be the target metrics of other teams. So if you run an experiment, cause everything we do gets AB tested and ran an experiment that helps you target metric, you gotta make sure that it doesn't hurt any of the guard rail metrics. So they have to be the velvet intuition. Teams have to develop an intuition of how other teams metrics move. So they know not to mess up with them and not to bring them down. So we basically create a system where everyone's incentivized to move everything up and not at the expense of something else. Watson: Gotcha. That makes a ton of sense because yeah, you're juggling all those metrics, but if we're talking to down to like the team level or the individual level, you can't have everyone looking at all things. They need that element of focus. So tell me a little bit about, you know, you joined the company a few years ago, it's been growing like a weed and there's a lot of excitement in Pittsburgh in particular about, you know, a potential future IPO. And that love what that means just for the Pittsburgh tech scene. But can you paint a little bit of a picture of where the product was when you got here, changes that have been made, that kind of take us to the present and then maybe we can talk a little bit about where it's going in the future. Mazal: Sure. Yeah. I mean, the product has made tremendous strides. Since I joined-- I don't want to take credit just because I joined is like correlation or share has custody, but it has been a tremendous amount of progress on the product side. Cause I mean, it's very collaborative. Everyone's involved in this, but you know, we were struggling in many fronts, honestly. Like we were trying to figure out a way to monetize. We weren't exactly sure how to do that, growth was a little bit like stagnating. And we were kind of stuck on how to teach better. Honestly, we were like trying to figure out all of these problems and everyone that tremendous amount of effort to turn all of these things around a little by little. So first on the morning, on the morning, the station side, we landed on the subscription business that has been very successful and we're able to continue to grow, on a consistent basis. On the growth side, we came up with-- I won't get into the details too much, but we have a fairly sophisticated growth model, that has a bunch of different metrics that we identified. We run modeling on it and identified a metric that turns out to be super high leverage, which is called CRR, CRR is the retention rate. And we put a team just optimized on that, to focus on that to optimize that metric. And that has resulted in people just staying with a product a lot longer. So when they come into the product, they get hooked on having like a Duolingo streak. And those, the number of people with a streak of seven days or longer, used to be about 20% of our DAUs and now it's about 60%. So people are just a lot more engaged with the products. They stay longer telling their friends more about it. And that has really super-charge our user growth. And what's cool about it is that it's growing faster than ever. It's growing super fast, but it's growing with better users, better and more engaged users. Right. Which is really a really healthy way to grow. So that was a lot of research by a lot of people and just a lot of creativity and problem solving. And then on the learning side, I think probably about half of our product teams in the company, work on learning. And that is really challenging because it's hard to measure learning. So we have to use a lot of just learning science research, intuition of the product ourselves, and coming up with kind of proxy metrics, provoke, believe your percents learning, and combining all of that together. And also being very systematic about how we think about languages and what is the language and how do you break up a language into its components and different levels of proficiency. So you can think about languages as vocabulary, a combination of vocabulary and grammar for enunciation, understanding sounds and being able to have skills like with that, like speaking, writing, reading, listening, and able to do that different levels of proficiency from beginner to advanced. And then we've systematically basically thought about that matrix of skills and levels of proficiency. And targeted each of those cells and just got better and better at all those things. And that has made a tremendous difference in how well we teach, where I think Duolingo is known for as the way to get started with a language and over time, we have more and more people say, wait, you can go a lot more, you can go a lot further with your language to Duolingo, than people in the past thought of or realized. Watson: And so as we kind of chart into the future, it sounds really like that ramp up from beginner, moderate, into really high level proficiency is the aspiration for where the product is going? Mazal: Yeah, that's a big part of it. We want you to be able to pick up Duolingo and get all the way to proficiency, to full proficiency, where you can go to a country and study there, or work there, travel there, and just feel like you're fully prepared, just using Duolingo. We're like maybe three quarters of the way there. Maybe I'm being a little bit generous on myself, but we're getting close. Watson: All right. So in terms of where the product falls, as we think more from like a business standpoint, this is very much in the category of like a consumer facing app individuals downloaded. They kind of have their own personal goal and that's where the interaction lies. But we started this off talking about the economic opportunities and the, you know, the potential, I would imagine for things more aligned at a kind of enterprise or B2B type of level. Is that-- how does that come into the consideration for Duolingo? Where does that kind of fit into the whole product framework? Mazal: It's a great question. And I'll answer it. Sorry to run it that way a little bit, but we have another product called the Duolingo English test. And this is a computer adaptive, fully online, AI proctored and human Proctored two test that you can take. It measures your English proficiency and that is accepted as as a sign of language proficiency in over 3000 universities and colleges. So it's become a significant part of our business now. It grew in the thousands of percent during the pandemic, which was pretty cool, because our competitors, you have to go to a testing center and you have to sign, and all those shut down. And it just became basically the only way you could demonstrate your English proficiency in the whole world for, for a few weeks. So, we believe that, how this connect to your question is, people who need to learn English, they need to also be able to demonstrate, certify that they know English. That needs to be in the resume, that needs to be when they're talking to employers or potential employers. Right? So them doing an English test, plays a big part on that economic opportunity angle. And what we're trying to do is that we call it," closing the loop," basically teaching well enough on the Duolingo app, that you can take the Duolingo English test and do very well on it. And we're just beginning getting to that point. Watson: So, I want to now kind of hone in on this role that you find yourself in because, you know, feedback that I've heard from listeners of the show is man, I love, you know, understanding what it takes to be the founder of a office, furniture wholesaler, or a tech startup, or what have you. To be chief product officer-- I keep saying the number, cause to me, this is just, almost anxiety inducing when I think of the scale of it-- but to be teaching languages to tens, hundreds of millions of people is an immense responsibility and a really kind of, I'd imagine, fantastically, intellectually stimulating role in which to be. So I I'd like to unpack a little bit and you can start wherever you know makes sense to you. But to me, you know, you have this background, you worked at Zynga which was a digital game company, MyFitnessPal-- I've used that to track a few runs, back when I was more into running, I haven't had the consistent habit, like you're aspiring to with Duolingo. But, and that's more a me thing than the product thing, can you talk a little bit about these past experiences and, you know, if chief product officer was the goal, like how did this come together to make you capable of filling this seat? Mazal: Yeah, so definitely a chief product officer was not the goal. And I was actually surprised when Louis said, Hey, I think I want to promote you to chief product officer. And it's like, really? Same thing happened with VP of product. I was like, what, you want to do this? So the--but to get to your original question of, how did it get here? It was just so many different things in life that build up to this. And I think it's just great coincidences in a way, you know. You can go as back as like, high school. I was learning English, I didn't grow up speaking English. And I was lucky enough to go to a school that did a pretty good job teaching English, and came to the US and realized I didn't understand. I could understand actually pretty well, but I couldn't really say much. And so I had that experience as an adult, of really being able to empathize with people who are learning a language and how hard it is and all the things that kind of catch you by surprise. Like, you know, for years, I could not understand the difference between a bag and a bug. I was just like, to me, it was the same word. It was like, people were just making fun of me. So anyway, I could empathize a lot with that experience. Then after I graduated from college, I ended up working in nonprofit, in the education sector, eventually leading an education program and coming up with curriculum and mentoring programs and just really diving into how people learn. Then went to grad school, discovered this thing called product management. Also, I did a master's in decision science. So I'm always being curious about how people think, how people make decisions and how you can influence people's decision-making for their own good. And so I studied kind of public policy and decision making together. But I got into product management somehow. This company, Zynga, that makes video games, I thought, I was like, oh, what an interesting laboratory of how people make decisions. And so I went to work there, really enjoyed the aspect of making games and how collaborative and creative it could be and how cross-functional, right. We had a team of, like, I remember for one feature, it was probably like 10, 12 people and everyone did something different. There was no two of the same. And, you know, you have artists and illustrators and animators and engineers and game designers. And it was just so fun. And then at some point, I remember people-- they brought to the office, some of our most valued users, which were people who had spent probably like over 50,000 to a hundred thousand dollars on this game. And I was like, to be able to spend that much money on a free to play game. This has to be consuming their entire lives. And I felt really terrible about it. I felt like, oh, I can't, I don't know that I can be part of this and feel good about it. As much fun as I was having making games, just seeing the impact that a very addictive thing could have on someone just didn't feel right. It wasn't what I wanted to be doing in my life. So soon after that, I quit and I went to work at MyFitnessPal, which you mentioned. And that was again, trying to use behavior change and decision science to make people have habits. But I wanted to make sure that these were habits that were good for them. So that's how I got into that job and enjoyed it. It felt like I learned a lot there. Then, you know, eventually moved, worked at a different company. I helped them build a PM function at that other company. And then Duolingo reached out, out of the blue and my mom was using Duolingo at the time to learn English. I was like, sure, well, let's chat and, it was like, I came here to Pittsburgh. I really liked the city, you know, coming through from the tunnel from the airport into Pittsburgh at night. And it's just like the lights. It was like, wow, this is like really cool. And the people are super nice, you know, it made me think a lot of just, east coast city, in terms of things that are available culturally. But the niceness and kindness of the people is very kind of Midwestern. And, it was like just the perfect combination. So yeah, I like the city, and I also felt like you brought everything together, right? That the language learning experience, dedication experience that I had, the gaming experience, experience building a PM function, product management, function, everything into one. So a lot of the things when I joined Duolingo came really intuitively. I just understood a lot of the things that people were talking about because I had lived them myself. And I think that has really helped being able to have impact at the company. And I would say--so I may be like rambling way too much, you can stop me at any time. Watson: I mean, the way you told that story, it reminds me a lot of the Steve Jobs' Stanford commencement address, when he talks about how you could have never planned it as you were moving forward. But looking in reverse, there's this very kind of obvious sequential interrelated amount of lily pads that kind of landed you at this current Lily pad. And I think that the, you know, I'm thinking about some different things: I'm thinking about habit building, I'm thinking about just like good design principles generally, and then I'm also really thinking about, you know, the human side of this. Which is there's the human users that you kind of had this experience at Zynga, seeing the effect on the humans in that regard. But then there's also the humans that work with you that work kind of on your respective teams and learning how to really get the most out of them, because it's very different than an entry level product role, where you're kind of got your little corner of responsibility. And now overseeing everything, it's much more about how do I coach, how do I incentivize, how do I recruit so that these product goals that I'm responsible for basically get fulfilled by the team members there. They're doing most of the heavy lifting. So tell me a little bit about that, tell me about the development as a leader and kind of how you've added that realm of skills. Mazal: Then how I help others become leaders, how I grew as a leader, or- Watson: I mean, I would say your growth as a leader is your ability to help other people become leaders and take that responsibility on. Mazal: Yeah, absolutely. That's a good point. So I think to be a good leader, you gotta be authentic to who you are. And for me, I'm someone who is very reserved and introverted. Someone who thinks a lot about feelings, and also very driven and ambitious, which is I think like a weird combination that throws people off. But so my approach to leadership is to basically understand what makes, well, what people are, what makes people tick, right? Why are they here? You know, why they're showing up to work to get what? And help them get that, whatever that is. Some people they-- and I do that because I care about them and I just, don't judge what it is they're here for. It's like, whatever it is that matters to them, I help them get there, because, you know, I care about them. And I think that makes people keep showing up at work and keep doing their best work. And that requires listening with empathy. It requires not judging. It requires honestly trying to help. So that's kinda my approach. Also, I think it requires taking care of their feelings, right? Like when you got to say something hard, you got to make people change their mindset or something. Some managers will be like, "Hey! You know, you got to change. This is not--you're not getting what you want, like deal with it." And I was like, well, what can I-- I don't go and do that. I just take some time and think, how can we turn this into a win-win situation? Right. And I was like, "hey, you're not, maybe you're not getting the thing that you wanted, the win that you wanted, but can we create another win that can help you grow in other ways that you also wanted to grow? So. That's one part, right? And then the other part now is helping managers to be able to do that for the people that they're managing and encouraging them to really get to know the reports and listen to them and to understand not just how they feel, but why they feel the way they do. How are they seeing the world, that the facts are being interpreted in a way that generates the feeling that they're having, and help them understand where in that needs to be worked on. And we're like, well, maybe we need to change the facts. Maybe we need to change the way the facts have been interpreted with, with new facts that they're not aware of. And we need to help them and understand that the feelings they are having are reasonable, but there's other feelings that could be reasonable to have as well, right? And focus on the thing that makes you happy, right, and grow from there. So anyways, that's like a bit of a rambling answer, I apologize, Aaron, but happy to dig into any of those things more deeply if that would be helpful. Watson: Yeah. But it really, you know, what I'm hearing again, is one of your metrics for the app is retention, right? And part of retention is predicated on being deeply empathetic to the user. If you understand what they're actually looking for, and you're able to give it to them, then that's going to keep them coming back cause you're delivering the goods. And it's the same idea where, you know, the empathy for those team members. And that's a huge topic of conversation. I feel like it's been that type of conversation for a decade now, but it's like people are job hopping. People are, you know, going from thing to thing. And one of the biggest advantages or levers, or kind of points of opportunity for a company, is the ability to recruit and then retain great talent. It's part of how you beat your competition, is we were a team with chemistry that had been thinking about this problem for three, four, or five, six years, as opposed to six months, 12 months, 18 months. It's just going to lead to better decision making. And, you know, it's the same. Those two things are obviously interrelated, but it requires the same kind of core skillset of empathy. Mazal: Absolutely. Yeah. And, I'll tell you something that I've learned at building in terms of that. I never really grasped this before working here, and it's: my imperfections generate some sort of pain or discomfort or problems for other people, and then having empathy for the pain I generate on them, and being humble about that. It's something that I've been learning, and it's been very transformational for me to like just lean in into that uncomfortable situations, like, oh, I am the cause of your pain. I'm the cause of your discomfort -- and listening to change. And that's been something really great about working at Duolingo where I felt like they--Louis has had patience with me, as I worked through the things that I need to work on. And I realized that at some point I have felt like embarrassed or wanting to hide those things, but it actually doesn't help. Like the more open and transparent you can be by the things you're working on, the better others feel about sharing what they're working on, the more they feel they can share it. And also they're going to have more patience with you, because they know at least you're working on it, right, and that really helps keep a team together. Watson: Beautiful. I have one more line of questioning and then we can kind of aim towards wrapping up here. And that's the idea of constraints. We've been-- we've explored this in so many different ways, you know, a nascent startup they've got every constraint in the book, but you know, all the way up to people making geopolitical decisions. There's always some sort of constraint that's in place for a company like Duolingo. And more specifically for someone in the role that you are as chief product officer, your team, like you said, has grown 10 X. Since you've joined the team, I don't know the exact number, but you as a company have raised tens of millions of dollars. How would you list or prioritize or explain the constraints that are facing you, in the present, as a company that has, you know, more funding than 99% of, of startups out there? And, you know, these kind of other obvious resources that unlock some constraints, what are the constraints that face the org and maybe you as the chief product officer generally? Mazal: Hmm. Great question. So the major constraint almost in a way, it's like what-- your mission, right? Like the, who you're trying to be and what you're trying to do. You could think of it as a constraint as well. That tells you lots of things you cannot do, because you don't want to do them because they're against who you want to be and why you want to achieve. The next step, there, I think is we're constrained by the amount of information that we have. And that's something that I've been very proactively trying to work on at Duolingo, by building new functions, like data science and UX research, and really being an advocate for like our learning science team as well. Because the more information we have... at the beginning, it really felt constrained by, we don't know a lot. We need to learn more faster. So information I think is key, and making sense of that into frameworks, into strategies, into plans, et cetera-- so processing that information too. The next big constraint is people, right? Getting the right talent on the right seats at the right time is obviously extremely challenging, and there's lots of things that we would want to do more of, but maybe we can't because we haven't found the right person for it. So hiring is key. And I think-- that's it, yeah. Watson: Interesting. Yeah. I mean-- one of the lessons of life that I've slowly come to realize is everyone has the constraints. There is no kind of boundless entity, God, that that's walking through the world in some way or shape or form unconstrained-- maybe Bezos, maybe one day I'll get to ask Bezos what his constraints are-- but the planet earth, perhaps with the blue origin, rocket or whatever. But, yeah, it's an interesting kind of thing to reflect on. And, I I'm guessing that you won't make any sort of comment on this whatsoever, but I do suspect that there is a kind of next chapter for Duolingo as a company, generally hitting the public markets at some point in the future, that I know that the folks in Pittsburgh are very excited for, and what that will mean as for the city of Pittsburgh, for the company, Duolingo, for all the constraints that you guys continue to face and hopefully unlocking some of those. Mazal: Sure. I hope so, yeah. Watson: Cool. Well, before we ask our standard last two questions, is there anything else you were hoping to share today that I just didn't give you the chance to? Mazal: We're hiring? Yes, Duolingo's always hiring. So check out our job post on our website. Watson: Right on. Well, that's the next question-- digital coordinates where people can connect, learn more, follow along with what you're doing. Obviously, download the app and start learning another language if you aren't already doing so, but what other coordinates can we point people towards? Mazal: Yeah. I would say download the app and find me and follow me, I'm Jorge Mazal on the Duolingo app, you can find me there. Watson: Right on. We're going to link that in the show notes. I'm actually not quite sure how to link that one, usually I'm like, oh, it's just a LinkedIn profile or something, but I'm going to try to figure out how to do that with the Duolingo profile, if I can make an external link or not. But, that's all going to be linked, going to put their.com/podcast for every single episode of the show. Or in the app, or you're probably listening to this right now, but before I let you go, I want to give you the mic one final time to issue an actionable personal challenge to the audience. Mazal: Hmm. So I had a wonderful experience last week where I really took like a significant amount of time to help someone with something that they really needed. And it was-- It was great. It just felt so good, especially if they're being isolated for so long in the pandemic to do something that-- we're just helping someone feel better. And the challenge that I would have for the audience is can you block three hours, half a day to do something that will make someone else feel really good, without having any expectation of return. And just getting that perspective again, that we're all in this planet together. Service is what makes us human and it makes you feel best at the end of the day. So that's my challenge. Watson: Yeah. Have you ever heard of the book, the five love languages? Mazal: I have. Yeah. Watson: Yeah. So acts of service, I'll go to the grave saying it's the most underrated one in terms of being able to convey love. Not that there's anything wrong with gifting or words of affirmation or any of those other ones, but it definitely takes I would argue more of a lift than some of the other stuff .And so I absolutely love that challenge and I hope that a bunch of people will take it right. Well, thank you so much for coming on the podcast, Jorge. I really, I learned a ton and I am excited for the future, you and the company. Mazal: Thank you, Aaron. It's been a pleasure. Anytime--happy to come back anytime. Watson: Awesome. We just went deep with Jorge Mazal, hope everyone out there has a fantastic day.

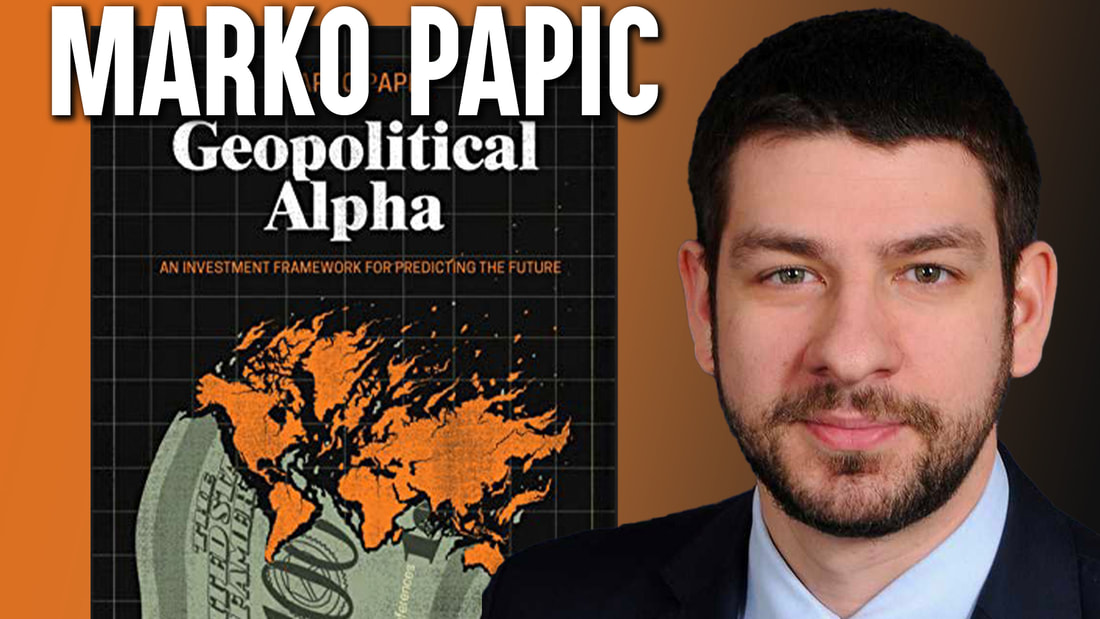

Marko Papic leads the strategy team at Clocktower Group, an alternative investments firm. Clocktower offers long-term strategic investment strategies to their clients, investment managers and institutional allocators.

Marko brings his constraints framework, outlined in his book Geopolitical Alpha, to analyzing the geopolitical trends of the day. His ability to accurately forecast major political events has enormous ramifications for portfolios. In this episode, Marko and Aaron discuss how the future of China-US conflict, Turkey’s geopolitical prospects, and how to break into the geopolitical analysis field. Sign up for a Weekly Email that will Expand Your Mind. Marko Papic’s Challenge; Spend time around people with the opposite political and cultural perspective of you. Connect with Marko Papic

Linkedin

Geopolitical Alpha book If you liked this interview, check out our interview with Mike Green where we discuss Bitcoin and index funds. Text Me What You Think of This Episode 412-278-7680

Underwritten by Piper Creative